The history of world drama is a continuous dialogue between tradition and innovation. Ancient tragedians laid the foundational principles of theatre; medieval stage traditions reworked them to fit religious and moral purposes; and the Renaissance restored interest in the human being as a carrier of contradictory passions. At the intersection of these traditions stands William Shakespeare — a playwright who reimagined the legacy of the past and transformed classical dramatic architecture into a flexible, psychologically rich form.

Shakespeare did not destroy ancient canons; he treated them freely, strengthening those elements that served the revelation of inner conflicts and weakening those that restricted narrative dynamics. His legacy demonstrates how ancient structural models can become the basis for multilayered works that remain alive regardless of era.

The Classical Foundation: Structure and Its Transformations

The Classical Foundation: Structure and Its Transformations

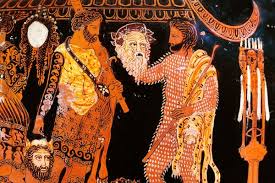

Ancient drama in Greece and Rome relied on a stable compositional framework: prologue, parodos, alternating episodes and stasima, and the exodos. The chorus held a central role, functioning as commentator, moral guide, and emotional mediator. Greek tragedians strictly adhered to the three unities of place, time, and action. Their drama was less psychological and more symbolic: characters embodied archetypal traits — resilience, pride, wisdom, resignation to fate.

Roman playwrights like Plautus and Terence introduced greater dynamism yet maintained a strong degree of theatrical convention: plots evolved within a limited set of masks and narrative schemes. The ancient approach was closely tied to myth, and conflicts were presented as manifestations of eternal laws.

Well-versed in classical heritage, Shakespeare employed its elements not as rigid rules but as creative resources. In Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra, for example, he approached the historical scope of ancient tragedy, yet removed the chorus and broadened the action across multiple centers of tension. Shakespeare ignored the three unities deliberately, aiming to convey the complexity of human motives and the nonlinearity of historical processes.

His interaction with ancient models reveals a new understanding of drama — one that emphasizes psychological depth, narrative multiplicity, and a dynamic vision of human nature.

Table: Key Elements of Ancient Drama and Shakespeare’s Use of Them

| Element of Ancient Structure | Role in Classical Drama | Shakespeare’s Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Unity of place, time, action | Structural clarity, controlled narrative space | Frequently violated to enhance dynamism and scale |

| Chorus | Commentary, moral orientation, reflection | Largely abandoned, replaced with introspective monologues |

| Archetypal characters | Embodiments of universal traits | Enriched with psychological complexity and ambiguity |

| Mythological foundation | Reinforced symbolic meaning | Often retained, but blended with realism and daily detail |

| Restrained emotional expression | Elevated and formalized tone | Expanded to include strong passions and individual voices |

This transformation demonstrates that Shakespeare viewed ancient structure not as dogma but as a point of departure, using its forms as raw material for innovation.

Medieval Tradition: From Morality Plays to Human Drama

Medieval European drama (5th–15th centuries) moved away from classical rationalism toward religious and moral content. Mystery plays, miracle plays, and moralities focused on salvation, moral struggle, and symbolic oppositions between virtues and vices.

Yet medieval theatre also introduced elements crucial to Shakespeare: large ensemble scenes, the blending of comic and serious tones, the use of allegory, and direct engagement with spectators. The medieval stage gave rise to the figure of the fool — a character mixing humor, philosophical insight, and the ability to speak truths inaccessible to others.

Shakespeare adopted many of these features, particularly the flexibility and tonal diversity of medieval performance. In King Lear and Hamlet, certain characters echo the function of moral guides, yet Shakespeare reimagines them as fully human, with personal motives and weaknesses.

Medieval theatre contributed fragmentation, multiple narrative layers, and an open dialogue with the audience — all elements Shakespeare expanded. But again, he avoided rigid formulas, allowing genres to merge freely. The fusion of medieval theatricality with ancient compositional logic helped shape his unique dramatic structure.

Renaissance Freedom and the Birth of a New Dramatic Form

The Renaissance widened the horizons of dramatic art: theatre became a space for social interaction, political reflection, psychological exploration, and artistic experimentation. Humanist philosophy placed the individual — with all their contradictions — at the center of dramatic action.

Shakespeare embodied this Renaissance spirit. He drew on classical material but filled it with vibrant emotion; he inherited medieval forms but replaced allegories with complex personalities. His dramatic architecture became a hybrid — multilayered, dynamic, and sensitive to context.

A crucial innovation was the psychological monologue. Where the ancient chorus once offered collective commentary, Shakespeare revealed truth from within the character. Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” serves as a moral framework in itself — not a collective voice, but an individual wrestling with existential dilemmas.

Shakespeare also mastered the art of maintaining multiple plotlines at once. In Romeo and Juliet, the lovers’ personal tragedy intertwines with the feud of their families, Verona’s political tensions, and the social fabric of the city. In Macbeth, psychological downfall develops alongside themes of power, guilt, and prophecy.

Shakespeare further broke tradition by adding realistic everyday scenes that disrupted the notion of “pure” genre. His worlds contained tragedy and comedy inseparably, just as in real life. This flexibility became a defining element of his dramatic structure.

The Impact of Shakespeare’s Structural Innovations

Shakespeare did more than modify dramatic structure; he proposed principles that shaped future eras. His influence extends to 17th-century classicism, 19th-century romanticism, 20th-century modernism, and postmodern experiments.

His rejection of the three unities paved the way for panoramic narratives. His psychological depth inspired realist dramatists like Ibsen and Chekhov. His genre blending contributed to hybrid forms prevalent in contemporary theatre.

Crucially, Shakespeare broke the notion of drama as a closed system. In ancient works, structure expressed inevitability; in medieval plays, it expressed moral clarity. Shakespeare showed that structure is a living mechanism — one that must adapt to human complexity rather than constrain it.

Conclusion

Shakespearean drama represents a thoughtful synthesis of ancient order, medieval theatricality, and Renaissance humanism, transformed into a new artistic system. His plays preserve links to classical tradition yet reject its limitations. He created a structure capable of housing contradictions, psychological depth, historical scope, and human frailty.

This adaptability and multilayered nature explain why Shakespeare’s works remain contemporary centuries later. His flexible dramatic architecture continues to shape theatre and literature worldwide, proving that structure is not a rigid frame but a living instrument capable of revealing new dimensions of human nature.